|

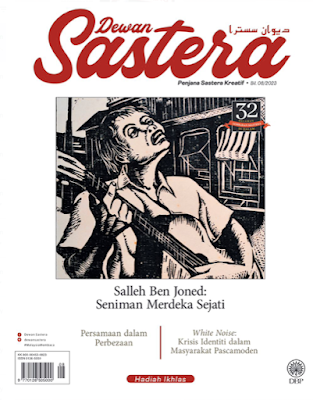

| (Photo credit: James Lee) |

SBJ would have turned 80 today, the 5th of July, 2021. On this occasion, we thought you might enjoy this article, newly penned by his sister Alima Joned, who was profoundly inspired by her brother’s fearless and unrelenting (but level-headed) pushing of the envelope within a face-saving, speak-no-evil cultural context.

Arguably, Malaysia has stringent censorship laws.

The most notorious on the long list of these laws is probably the Sedition Act of 1948. The Act expands free speech limitations to cover speech that has “seditious tendency,” a term defined to include the questioning of certain politically-sensitive issues such as the national language, and the rights and privileges of Malays and the natives of Sabah and Sarawak.

Constitutionally, a "Malay" must be a person who professes the Islamic faith, habitually speaks Malay, and conforms to Malay customs. Thus, any discussion regarding the Malays is likely to involve Islam. These two themes, the Malays and Islam, are major motifs in my late brother Salleh Ben Joned’s prose and poetry.

It may be a mystery to some why Salleh was allowed to deal with these themes without once running foul of the Malaysian authorities. He himself didn’t feel constrained by Malaysia’s stringent censorship laws. In fact, in "Testing the Parameter" (New Straits Times, 5 June 1991), these laws were not Salleh’s main complaint.

Rather, he was most concerned about the disease of self-censorship that appeared to have afflicted Malaysian writers of his time. So insidious was this disease that even when their periok nasi (rice bowls) were not really at stake, some Malaysian writers felt themselves unable to write freely. In a situation such as this, according to Salleh, the writer’s intelligence and moral integrity are at stake. According to Salleh:

Self-censorship is a universal disease, but I believe its local manifestation is quite peculiar, very “Malaysian” in an unflattering sense of the word. And what’s more, it’s becoming quite insidious. Those infected with this disease don’t always realise it; even when they do, they try to pretend that it’s unavoidable or justifiable. One can understand the self-censorship if the “integrity” of the writer’s periok nasi (rice bowl) is really at stake. But when it isn’t and yet he still censors himself, one questions not so much his moral integrity as his intelligence. Basically, it’s a question of perception – perception of what constitutes risks or dangers and the problem with our writers and literary middlemen… is that too many of them tend to perceive dangers too readily.

Perceiving Dangers Too Readily

Salleh himself was at little risk of being accused of perceiving dangers too readily. Throughout his career, Salleh wrote on two taboo subjects: race and religion.

The fact that his popular column, As I Please, appeared in an establishment newspaper indirectly controlled by the government was evidence that, handled correctly, these two themes can be a subject of public discourse.

I, too, am trying to avoid readily perceiving dangers when expressing my opinions, notwithstanding a couple of insulting and discouraging personal experiences. I list two examples:

In 2007, I was invited to speak at a seminar to honour the late Professor Tan Sri Ahmad Ibrahim. The host, the Institut Kefahaman Islam Malaysia, as planned, subsequently published the seminar papers in a book. My paper was excluded from the collection. Why my paper was excluded was not entirely clear to me.

Perhaps the IKIM leadership had been troubled by my introduction, in which I described the image I had of this giant of the Malaysian legal world in the following words:

….[T]he picture of the late Professor with his songkok instantly came to mind. Indeed, the beloved late Cambridge-educated Professor Ahmad was never seen in public without his songkok. His constant wearing of songkok coupled with Western-style attire [of shirt-and-necktie] suggested both cultural and religious significance as well as the co-existence of the secular and the religious in his mind. Regardless of what it could suggest, the image surfaces whenever I think of secularism in the Malaysian context.

Or perhaps the IKIM leadership did not like my position that, notwithstanding the claims of successive Malaysian political leaders, Malaysia was not an ‘Islamic’ country; and that no matter how we look at it, the canvas of Malaysia was one that showed a picture of the secular and Islam existing side by side. Either - or something else - might have been perceived as a threat to the periok nasi of the IKIM leadership.

My own (modest) periok nasi was certainly not threatened. Although surprised, I was not upset when told about the exclusion of my paper. The paper was easily accepted for publication by the Universiti Malaya law faculty’s journal instead.

This same journal also recently published an unsparing critique I made of a certain judgment of the Malaysian apex court. In my view, this judgment could not be supported by fundamental legal principles, and if left uncorrected would undermine the rule of law and further confuse the line between the secular and the religious in the Malaysian Constitution.

My Legal Analysis of the Bin Abdullah Case

Last February, the full panel of the Federal Court handed down its decision in Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara & Ors v A Child & Ors (Majlis Agama Islam Negeri Johor, intervener), the case commonly known as the bin Abdullah case.

Readers may recall that children’s and women’s advocates were dismayed when the Federal Court left a Muslim infant without a patronymic as is customary for the Malays in Peninsula Malaysia.

The bin Abdullah case began when a Malay child, a boy, was born less than six months after his Malay parents’ marriage.

Father MEMK and mother NAW subsequently registered the child’s birth.

When the birth certificate was issued, MEMK and NAW discovered the Registrar-General of the National Registration Department had changed their child’s name. Instead of having his father’s name as the child’s patronymic (as his surname), the child was given the patronymic “bin Abdullah.”

Upset and distraught, the parents requested the Registrar-General to make the necessary corrections. The Registrar-General refused on religious grounds.

(Apparently, the understanding of the Registrar-General was that under Islamic law, a child is illegitimate if born less than six months after the marriage of his/her parents, and thus the patronymic `bin Abdullah’ or `binti Abdullah’ - depending on the gender - should be given to that child.)

The parents applied for judicial review in the High Court.

Undeterred by the High Court’s dismissal of their application, the parents appealed to the Court of Appeal.

There the parents prevailed. The Court of Appeal unanimously ruled that the Registrar-General had acted outside of his statutory powers. In essence, the Court of Appeal ruled that at issue was the duty of the Registrar-General to register births in Malaysia, which was governed by a specific federal statute. This statute provided the Registrar-General no powers to change the name of any child, according to the Court of Appeal.

The Court of Appeal was correct in my view.

However, on further appeal by the Registrar-General, the Federal Court ruled, in a narrow majority of 4:3, that Islamic law governed in this instance.

I wrote a commentary on the Federal Court’s decision, critical of the majority opinion and once again this was published in the Universiti Malaya law faculty’s journal.

My critique was also leveled at the Registrar-General, the bureaucrat who had no business to take it upon himself to be a law enforcer (Islamic or otherwise), never mind that he was using his official time to calculate when exactly the boy was conceived. Nothing in the statute that created his office gave him power to do what he did.

My modest success in getting the bin Abdullah commentary and the tribute to the late Prof. Ahmad Ibrahim published, leads me to conclude that it is entirely possible to initiate and engage in public discourse on the subjects of race and religion, if we do so in good faith and our views are well-grounded.

Controversy is Good for Malaysia’s Intellectual Development

When it comes to banning books about race and religion, Malaysia’s record is mixed. Kassim Ahmad’s Hadith: Satu Penilaian Semula (Hadith: A Re-evaluation) is one book that was banned. Tun Dr. Mahathir Mohamad’s The Malay Dilemma was initially banned, but the ban was subsequently lifted. However, Dr. M. Bakri Musa’s The Malay Dilemma Revisited: Race Dynamics in Modern Malaysia was never banned.

There can be more than one theory to explain the mixed record. In Malaysia, controversy is likely to ensue when writing about race and religion. But people like my brother Salleh Ben Joned continued to write despite the risk of controversy.

He was of the school of thought that understands that controversy in the form of discussing opposing views, is in fact good for Malaysia’s intellectual development. He believed such discourse should be welcomed unless it could cause a riot or bad feelings among the races. And this deeply-held belief guided Salleh in his writing career as a poet and an essayist.

Many people were surprised that my brother was allowed to write essays and columns on taboo subjects and to do so openly in an establishment newspaper like the New Straits Times. In the Preface to As I Please, a collection of his select writings published in 1994 by Skoob Books (London), Salleh responded to this surprise:

The fact that an intelligent man and a Malay (it’s worth noting), was chief editor of the paper explains the freedom I was tacitly granted. Not a few readers praised me for my so-called ‘courage’; I personally didn’t think it was a matter of courage. Commonsense – that’s basically what’s needed. That, and a real concern for the intellectual state of the country. I was furious when V.S. Naipaul, interviewed while in Malaysia researching for his book Among the Believers, so casually said that mine was “a country without a mind.” But I knew what he meant, and if we confine that remark to the contemporary scene I couldn’t help but agree with him.

Salleh opined that if self-censorship in Malaysia was bad for the general intellectual development of Malaysia, it was worse for the development of Malaysian literature. Rather than being sentimental, emotional and unprofessional, writers – Malay writers especially – have the responsibility to use their craft to tackle these taboo subject matters, notwithstanding the discomfort or the controversy the subject may engender.

* * *

My brother was always testing the parameters. He survived Malaysia’s stringent censorship because he was extremely well-read and a gifted writer. Using his art craftily, so to speak, and with poetic playfulness, he was able to exploit the limited freedom that existed in Malaysia while staying true to his calling. In encouraging others to also always be testing the parameters, he wrote:

We all know that our censorship laws are very stringent. But while hoping (and fighting?) for greater liberalism, it’s not impossible to learn to live with them while we have to. You would be amazed what can be done within the existing restrictions. It’s up to writers and publishers to exploit the limited freedom that exists. In other words, to “test the parameters” – or the perimeter of the permissible.

I am not a writer. I also live abroad. But I, too, despite setbacks and insults, continue to test the parameters. In my own field of law I have been inspired by my brother’s call for all of us to care for Malaysia’s intellectual development and do our best to contribute to it. Privileged with some education, I feel a certain obligation to do so.

My brother was a champion of kebudayaan rojak (multiculturalism). He was a patriot with a vision of a united Malaysia where Bangsa Malaysia lives in peace and harmony. If we share this vision, we too should test the parameters. Together, we can help build a truly functioning democracy that would be the envy of the world.

Alima Joned is a lawyer in private practice in Washington, DC.