|

| Mural found in Jakarta commemorating Chairil Anwar |

Two Sundays ago, April 28, at about 3 p.m.,

I had a “visitation.” Sort of. It was one of those boring suburban Sunday

afternoons, and oppressively hot. After a heavy rich lunch, I felt like having

a good siesta, which I often do, in the good old tradition of my lazy

ancestors. But the noise of the telly from my next-door neighbour (probably a

repeat of some excruciatingly silly Drama

Swasta (TV Drama) was unusually loud; it was impossible to sleep. The heat,

the boredom, and the damned silly telly – it was enough to drive you mad. In

fact, for a spilt second, I almost felt the onset of vertigo. I had a flash of

a vision, of myself leaping across the room like a tiger, snatching the

ancestral kris gathering dust in the corner of my study, storming into the

street running amok. I didn’t do it.

The threatening vertigo mercifully passed.

I covered my ears with a pillow, and tried to retreat into my own world. Then a

line or two of a poem by a long-dead Indonesian poet unsurprisingly came to

mind: “Aku ini binatang jalang/Dari

kumpulannya terbuang…” (I am a wild beast/ Driven from the herd...) I

thought of a poem of mine, written at one sitting a few years ago, on a Sunday

afternoon exactly like April 28, a poem with the same title as the Indonesian

one, Aku (“Me”), its opening and

closing lines in fact parodying those of that poem. My Aku was actually an “updating” of the other Aku. If the Indonesian Aku (written

in 1943) was the defiant cry of the individual spirit, its sheer refusal to

conform, my Aku is just the opposite.

It’s the aku of the era of the NEP –

a good pious, patriotic “Bumigeois” who sits in front of idiot box every Sunday

afternoon, and every evening, his mouth gaping wide, a box of KFC in his lap,

drooling and finger-licking his existence away and dreaming of going on like

that for another thousand years. (The closing lines of the Indonesian poem read:

“Dan aku akan lebih tidak peduli/ Aku

mahu hidup seribu tahun lagi.” (And I don’t care a damn/ I want to live

another thousand years.)

Thinking of the two Aku’s, I suddenly felt a rindu

(nostalgia) for the long-dead poet. It had been years since I last read his

stuff. So I went into the study and pulled out the yellowish disintegrating

copy of the book that I had been carrying around with me ever since my school

days. With the pillow still covering my ears I went through the poems again,

and flicked through the few pages on his life and times. It was then that I

noticed the date of his death. April 28, 1949. The coincidence wasn’t quite

earth-shaking, but it was, I felt, a bit uncanny. Chairil Anwar, my much missed

brother, was the coincidence a sign of some kind? Yes, Chairil Anwar – that’s

the name of the poet. Chairil Anwar. Lovely name. The best of lights. Chairil

Anwar.

His poetry, believe it or not, used to be

studied in our schools; he has been translated into English (notably by the

American Burton Raffel); and for a long time after his death he was a figure of

legend. Yet I am sure there are many people in our country today who have never

heard of him, let alone read his poetry. Among Malay sasterawan, dilettantes and literary hangers-on, the name Chairil

Anwar is still spoken of in some awe. They can recite lines and whole poems by

Chairil – especially the notorious Aku.

I doubt that what Chairil stood for, and what poems like Aku are saying, really means very much to these people. After more

than 40 years, the defiant absolute honesty of Chairil Anwar is still a

challenge. A lonely figure in the Forties, when his country was fighting for

its independence and the poet for his, he remains without peer, or true

spiritual descendant in the history of modern Malay-Indonesian literature. He

was the first, and probably the only, true bohemian and rebel the Malay

literary world has produced. (Our own Latiff Mohidin is the nearest to a

bohemian we have had; at least he was one until a few years ago, and in a sense

he still is, in spirit at least, despite what appearance might suggest.)

Being a “bohemian,” like a bourgeois, is

more a state of mind and spirit than that of your bank balance. The true

bohemian treasures his independence in every sense of the word. It’s just an

unfortunate fact of life that this independence often means a poor bank

balance, or no balance at all. Chairil

Anwar literally lived from hand to mouth in the Jakarta (or Batavia) of the

1940s. He was a familiar of prostitutes on one occasion (so legend has it), he

had to sell his last shirt to pay for his nasi

bungkus (cheap rice dish): and he died of not one dreadful disease but four

– tuberculosis, typhus, cirrhosis of the liver, and of course syphilis. He was

only 27.

I think it is at least arguable that the

health and vitality of a nation’s literature can be gauged by the existence or otherwise of non-conformists among its writers; non-conformists who may

have to be sick in body, due to deprivation, but alive in spirit. I am not, of

course, suggesting that in order for our literature to be more alive and

exciting than it is today, we have to have a few amoral bohemians who fornicate

with total abandon in pursuit of that elusive poetic masterpiece, snatching

what crumbs of rice he can on the way dying of syphilis (or AIDS, as it would

be today) with the bloodstained, pus-stinking manuscript of his final poem in

unrepentant hands.

That bit about having to be sick in body

for the sake of being vital in spirit was, of course, just a manner of

speaking. It’s the willingness to suffer for the sake of fiercely-held values

that matters; and the suffering doesn’t have to mean being incarcerated in

prison, or even literally starving in some stinking squatter hut. Willing to

suffer and at the same time able to enjoy life, to affirm its essential worth

despite all its contradictions, pains and frustrations. That, I believe, was

what Chairil Anwar somehow managed to do. Here’s one or two anecdotes that

suggest the spirit of pure spontaneity that was Chairil Anwar. A contemporary

remembers him perched precariously on the edge of an open car, and shouting the

poems of Walt Whitman or Rilke into the wind and the polluted streets of

Jakarta. Another remembers him hiring a whore and making love to her in a park,

just to know what it was like to make love in public. Dreadful behaviour, but forgivable, I think

in a poet like Chairil – he can get away with it. There was something

recklessly noble, beautiful even, in his personality. As a poet and polemicist,

his voice could be harsh and grating, but was also capable of incredible

tenderness. Read the prose pieces addressed to Ida, as well as the poems of his

relationship to women and to God.

On the subject of women and God, and death

too, Chairil could be searingly honest. None of the sentimentality and

predictable pieties with him. And the language and form, refreshingly

revolutionary for its time, perfectly match the honesty of mind and heart. On

the subject of the inscrutable God: “Ku

seru saja Dia/ Sehingga datang juga/ Kami pun bermuka-muka… Ini ruang /

Gelanggang kami berperang/ Binasa-membinasa/ Satu menista lain gila.” (Di Masjid). “I screamed at Him/ Until he

came/ We stare at each other, face to face... This/ Is the ring where we must

fight/ Destroying each other. One spitting insults, the other gone mad.” (At

the Mosque). The double meaning in “bermuka-muka”

inevitably lost in translation, is characteristic of the fierce honesty of

Chairil; the Malay phrase means both “face to face” and “pretending,” or

“putting it on.”

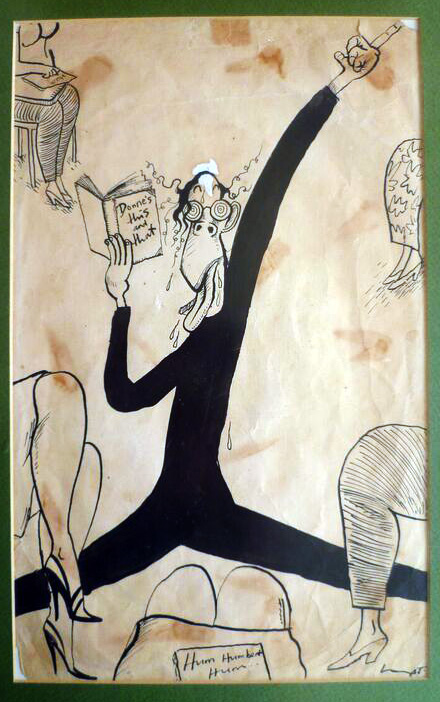

|

| Charcoal sketch by Salleh Ben Joned |

On the subject of women and love, have a

look at Kupu Malam dan Biniku (A

Whore and My Wife) and Bercerai

(Parting). He wrote a second Aku

which I believe not many people know of. “Ku

jahui agama serta lembing katanya/ Aku hidup/Dalam hidup di mata tampak

bergerak/ Dengan cacar melebar, barah bernanah/ Dan kadang satu senyum ku

kucup-minum dalam dahaga.” “I keep away from preachers and their holy

words/ so unsparing, drunk on sins/ I live/ in the very eye of the day/

whirling at the centre/ pox gaping, boils festering/ And now and then a smile

blooms which I kiss/ From which, in my thirst, I drink.”

Chairil Anwar, I claim you as my brother.

May your spirit live another thousand years. And may you do something to inject

some sign of life into this dreadful, deadening smugness and complacent

conformity that is much of our literature today.